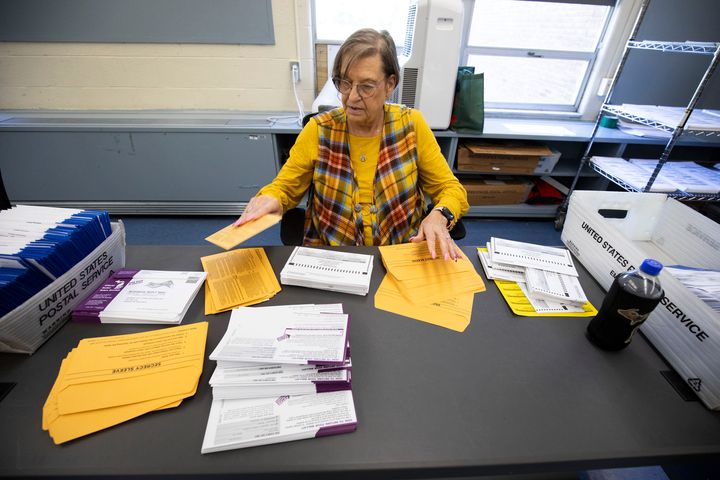

The pandemic election in 2020 marked a record-breaking year for the use of mail-in ballots, and voting via the Postal Service is still going strong. Still, some election officials are slightly on edge about this year.

Voting by mail is safe and effective, they emphasize — but amid a halting 10-year Postal Service reorganization plan that has impacted local mail facilities, and frustration over a lack of communication from Postal Service leadership, election officials have a crucial piece of advice for people voting by mail: Send ballots back to election officials as soon as you can.

“Give yourself at least a week” before Election Day to put your ballot in the mail, said Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon (D), the current president of the National Association of Secretaries of State. Some states will still count ballots with on-time postmarks that are received after Election Day — but it’s best not to chance it, especially since Republicans have sued in Mississippi to forbid this practice. The suit could have nationwide implications.

“Don’t delay. Get your ballot, research your ballot, vote it, and send it back in as soon as you can,” agreed Bryan Caskey, Kansas’ election director and the incoming president of the National Association of State Election Directors. “If you want to use the Postal Service, just don’t wait. Get it returned back as soon as you can — I would say [put it in the mail] at least a week prior to Election Day.”

The Postal Service agrees: “Our common-sense voter recommendation remains that domestic voters should mail their completed ballot before Election Day, and at least one week prior to the deadline by which their completed ballot must be received by their local election official,” Martha Johnson, a spokesperson for the Postal Service, told HuffPost in a statement.

Voters who are able can just skip the mail system entirely and return their ballots in person to election officials, or to a drop box, which is an even better solution, Caskey said.

Check your state’s rules about in-person ballot return options first — Tennessee is an outlier, according to the U.S. Vote Foundation, and requires mail ballots to be returned by mail — or just contact your local elections office and ask what’s best.

“The U.S. Postal Service is committed to the secure, timely delivery of the nation’s Election Mail,” Johnson said. “The Postal Service has been working in close coordination throughout the year with election officials across the country.”

To be clear, the Postal Service has a good record delivering almost all election mail on time: During the 2020 general election, 97.9% of ballots mailed from voters to election officials were delivered within three days, according to USPS data released the following January — and 99.7% of ballots were delivered within five days. For the 2022 midterm elections, it got nearly 99% of ballots to election officials within three days.

But with tens of millions of ballots going through the mail system right now for a razor’s edge election, every tenth of a percentage means a potentially election-deciding difference.

During primary election season this year, election officials across the country noted problems with late-arriving ballots. Caskey said 200 ballots ultimately weren’t counted in one of Kansas’ largest counties — despite voters having returned their ballots with time to spare. The Douglas County clerk said some ballots sent in July, ahead of an Aug. 6 election, were accidentally held and repeatedly scanned in the Kansas City post office. Overall in Kansas, nearly 1,000 ballots arrived too late to be counted, or were disqualified due to lack of a postmark.

The Postal Service’s official policy is “to try to ensure that every return ballot mailed by voters receives a postmark,” Johnson said — though this deviates from the policy for other mail, because postmarking usually depends on the type of postage used. Voters who want to make sure their ballot is postmarked can visit a post office directly and request one from a USPS employee, Johnson said.

What’s more, Caskey said, election officials’ concerns seemed to fall on “deaf ears” with regional Postal Service representatives.

“I do feel there was a lack of urgency during the primary,” he said. “Several states I know had specific problems with their primary and went to their regional [Postal Service representative], and it largely wasn’t responded to, and that is frustrating.”

Election officials have been raising concerns over mail-in voting for the past few months, mostly as a result of DeJoy’s 10-year cost- and job-cutting plan, “Delivering for America.” The foundation of the plan is rerouting mail through large, consolidated urban processing facilities, rather than smaller facilities that are often geographically closer to senders and recipients.

The overhaul has hurt on-time mail delivery rates, particularly in rural areas, and led to significant local protest. In August, after months of rolling out a plan to route Reno, Nevada’s mail through Sacramento, California — and encountering significant local objections and a lawsuit — the Postal Service finally scrapped the plan. In May, responding to lawmakers’ concerns about election mail, DeJoy paused further consolidation nationwide until 2025.

Still, the reorganization has already gone into effect in many places — like Oregon, an entirely vote-by-mail state.

Late last year, Chris Walker, the clerk in Jackson County, in the south of Oregon, was surprised to read in the newspaper about local Postal Service reorganization plans to route mail through Portland. Jackson County’s seat, Medford, is 273 miles away from Portland.

“My attitude is, although unfortunate, it is reality and the way life is right now for us,” Walker said Thursday, during a roundtable of local election officials convened by the Election Center, which is also known as the National Association of Election Officials. She stressed to HuffPost that USPS employees “do a fantastic job for us” and have been crucial partners during elections for years.

Mail ballots are set to be sent out Friday in Jackson County. The plan, according to Walker, is to send ballots, pre-sorted by ZIP code, directly to voters through a local processing facility, skipping the Portland detour on the first leg of ballots’ journey. Ballots returned through the Postal Service will be diverted through Portland, though — a big change from years past. Then, they’ll return to mail facilities in Jackson County and the surrounding area. From there, “USPS employees, in their USPS vehicles, will bring those directly to the election office,” she said. In the final days before Election Day, the returning ballots will also start bypassing Portland, and will instead be kept at the local level, Walker added. (According to the Post Office, this bypassing will actually start Monday for ballots returned in the mail.)

DeJoy’s reorganization isn’t the only headache. In September, election officials from across the country sent a letter to the postmaster general outlining a list of concerns, including inconsistent training for USPS employees on how to handle election mail, “exceptionally long delivery times” — including reports from multiple states of dozens or even hundreds of ballots received 10 or more days after being postmarked — and incorrect “undeliverable” designations for election mail that was being sent between election offices and voters’ legitimate addresses. “We continue to conduct ongoing field education and training on Election Mail processes for Postal Service employees,” Johnson said.

The Postal Service does have what it calls an “Extraordinary Measures” period for general elections, which this year starts on Oct. 21. On top of existing election year procedures — which include “all clear” checks, meant to ensure no election or political mail is left behind at post offices — the “extraordinary” period includes “additional collections, extra deliveries, special sort plans on processing equipment, and local handling and transportation of ballots,” Johnson said.

That covers areas like Jackson County, according to the statement: “Starting on October 21, return ballots that are destined to a local or nearby election office will bypass the processing operation and will instead be postmarked at the local unit and delivered to the election office.”

DeJoy, a major Donald Trump and GOP donor who was appointed to the postmaster general job by a USPS Board of Governors made up of Trump appointees, is a natural foe for Democrats and others anxious about election mail — particularly since Trump politicized mail-in voting in 2020, and lied that Democrats used widespread mail-in ballots to steal the election. During a hearing last month, Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Wis.) criticized a pilot program in the Green Bay area to cut down on the number of trips between Postal Service locations, which led to dramatic declines in on-time mail delivery.

“The first rockets that went to the moon blew up,” the postmaster general noted in his own defense. “That’s what [pilot programs] are for.”

“Thanks for blowing up Wisconsin,” Pocan responded.

It doesn’t help that communication with the Postal Service seems somewhat turbulent this year. A virtual Oct. 1 call between DeJoy and secretaries of state from across the country was “sort of command-and-control,” Simon, the Minnesota Secretary of State and NASS president, told HuffPost. “We were all muted. It was sort of a webinar [format]. It wasn’t as constructive as it could be.” Simon emphasized that the Postal Service and DeJoy have a “very tough job,” but said he and others were dealing with “unresolved issues” and looking for “more specific metrics or at least pledges as to election-related mail in particular.”

“I know what they’re capable of,” Simon said, referring to what he said was the Postal Service’s work in the 2020 election. “In 2020, there was more of a give-and-take, and more of an ability to have a real conversation, so it’s not as if they haven’t done this before under arguably much tougher circumstances.”

Still, DeJoy offered to connect individually with state election officials during the Oct. 1 call. And when Caskey and Kansas Secretary of State Scott Schwab (R) spoke with him last week, DeJoy was “very helpful” and responsive to their concerns, Caskey said. The Kansas elections director said he was “cautiously optimistic” about the coming weeks.

But as state election directors eye their fast-approaching deadlines for mail-in votes, there’s a noticeable sense of concern about how things will unfold, he added.

“All of us are just really nervous.”

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.