A judge in Harris County, Texas, the execution capital of the country, recommended earlier this month overturning a man’s death sentence, finding that he received ineffective legal assistance at trial.

In a highly unusual 158-page court filing, Judge Natalia Cornelio found that Jeffery Prevost’s court-appointed lawyers unreasonably delayed their investigation into mitigating evidence — information that may reduce a defendant’s culpability, including evidence of an abusive childhood, addiction, untreated mental illness or positive actions since the crime — and that the lead attorney, Skip Cornelius, “carried an excessive caseload” while representing Prevost. Those lawyers failed to uncover information about his mother drinking while pregnant with him and signs that he suffered from “brain deficiencies,” Cornelio wrote.

The Harris County district attorney’s office objected to Cornelio’s recommendation and urged the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) to deny Prevost relief. The district attorney’s office declined to comment.

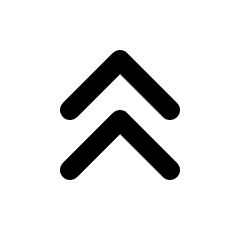

If the CCA agrees with Cornelio’s recommendation, 64-year-old Prevost’s death sentence will be overturned, and the case will go back to Harris County. At that point, the state could either pursue the death penalty again or offer a sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

Although allegations of ineffective assistance of counsel are common in death penalty cases, it is extremely rare for a judge to agree. The Supreme Court has held that to succeed on an ineffective assistance of counsel claim, the individual must prove that their lawyer was objectively “deficient” and that the outcome would have been different with a competent lawyer. Even when the evidence is compelling, judges are supposed to be “highly deferential” to the lawyer’s judgements and avoid second-guessing their strategy, according to the court. The standard is so high that even a lawyer admitting they did a bad job is often not enough to get their former clients a new trial.

Prevost grew up in a brothel owned by his grandmother, who pushed the women in the family into sex work, according to court documents. Prevost and his siblings were sexually abused as children. His father spent time in prison for heroin possession, and his mother had a violent temper, sometimes even shooting a gun at him. When Prevost was about 13, his mother was psychiatrically hospitalized after the death of his little sister.

In 2011, Prevost was charged with killing his ex-girlfriend, Sherry White, and her son, Kyle Lavergne. Like most people on death row, Prevost could not afford to hire a lawyer for the resource-intensive process of a capital trial.

Harris County, which executes more people than anywhere else in the country, does not offer public defenders in death penalty cases. Instead, the judge overseeing the case appoints defense counsel from a list of private lawyers. Defense lawyers whose livelihoods depend on indigent appointments often donate to trial judges’ election campaigns, creating a system that legal scholars have described as “judicial pay to play.” Many appointed defense lawyers maintain caseloads that far exceed state and federal guidelines, billing the state several hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to represent people too poor to hire a lawyer.

Death penalty cases typically have two phases: The first is to determine whether the accused is guilty and, if they are convicted, the second is to determine whether they deserve a death sentence. The trial judge in Prevost’s case, Mark Ellis, appointed Cornelius as first chair, and another lawyer named Allen Tanner as second chair. Prevost pleaded guilty and a jury sentenced him to death.

Cornelius was a subject of a previous HuffPost investigation into Harris County’s indigent defense system. Obel Cruz-Garcia, one of Cornelius’ former clients who is now on death row, told HuffPost he barely saw his lawyer ahead of trial. Cruz-Garcia, who maintains his innocence, alleged in a federal habeas petition that Cornelius failed to investigate and present information that could have undermined the state’s theory of the crime, as well as mitigating information that could have, at least, convinced the jury he didn’t deserve a death sentence.

Cruz-Garcia has been unsuccessful in appealing his sentence. Cornelius, who is no longer alive, previously denied allegations that he was ineffective in Cruz-Garcia’s case. In interviews, he dismissed the idea that his heavy caseload ever negatively impacted his work.

Tanner declined to comment on Prevost’s case, citing pending litigation.

Once sent to death row, it is exceedingly difficult to get that sentence overturned. In Texas, state habeas proceedings, which are the first opportunity to raise ineffective assistance of counsel claims, occur in the same court as the conviction, often with the same judge from trial. Both parties submit proposed “findings of fact and conclusions of law” (FFCL) for the court to consider before entering their own version. A 2018 review of 191 Harris County cases found that judges adopted prosecutors’ FFCL verbatim in 96% of cases the authors analyzed.

That is initially what happened in Prevost’s case.

After being convicted and sentenced to death in 2014, Prevost was represented in state habeas proceedings by public defenders in the Office of Capital and Forensic Writs (OCFW). He filed an application for writ of habeas corpus in January 2016, alleging that his imprisonment was unjust, in part, because he received ineffective assistance from Cornelius and Tanner at trial. He accused the trial lawyers of “woefully deficient” mitigation investigation that “left the jury with a remarkably incomplete picture of his life history.”

The court ordered Cornelius and Tanner to file affidavits, responding to allegations that they were ineffective. Both lawyers complied, supplying brief statements defending their work.

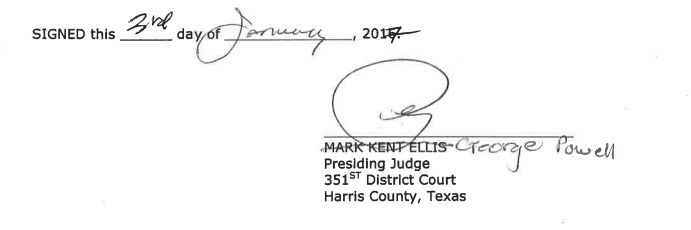

In November 2016, Ellis, a Republican, lost his reelection campaign to a Democrat named George Powell. The state filed a motion asking the court to set a deadline for both parties to submit their proposed FFCLs. Ellis agreed and set a deadline at the end of December, days before he was set to leave office. The state submitted its version, but Prevost’s lawyers repeatedly objected to the deadline, arguing it was premature to make a decision in the case, that the timing was motivated by electoral politics and that the deadline did not provide sufficient time to prepare their findings.

Powell assumed the bench on Jan. 1, 2017. On his first working day in office, he signed the state’s proposed FFCL verbatim, recommending that Prevost be denied habeas relief. Powell’s version still had the state’s header at the top of the document, and in the place that the state had left to Ellis to sign, Powell crossed out the former judge’s name and hand wrote in his own name.

Then, in a bizarre procedural move, Ellis, who was no longer a judge, also signed the state’s proposed FFCL and filed his version, which was identical to Powell’s except for the signature.

The two competing sets of judicial documents were both sent up to the CCA, which was tasked with deciding whether to follow the lower court’s recommendation to deny habeas relief.

In a March 2017 court filing, Prevost’s lawyers slammed the fact-finding procedure in the case as “indefensible,” noting that Prevost was not given the opportunity to cross-examine Cornelius or Tanner in an evidentiary hearing.

“One set of findings was issued by a newly-elected judge who had an impossibly short period of time to review the voluminous trial record and post-conviction pleadings,” Prevost’s lawyers wrote, noting that the case record was more than 7,000 pages long. “The other set of findings was issued by a former judge who was no longer on the bench. No matter which set of findings controls, Mr. Prevost was deprived of basic due process and adjudication of his claims of constitutional confinement.”

Later that year, the CCA remanded the case back to the trial court to develop more evidence related to Cornelius and Tanner’s work on the case. The appellate court also instructed the trial court to clarify which set of judicial findings should be considered.

Powell deferred to Ellis’ findings of fact and conclusions of law and directed Cornelius and Tanner to file additional affidavits. Prevost pushed for an evidentiary hearing, which would provide the opportunity for cross-examination.

Then, the case languished for three years.

During that time, Cornelio, a former public defender in Houston, beat Powell in the Democratic primary and went on to win the general election. Shortly after she assumed office in 2021, the CCA ordered her to promptly resolve the case. Unlike her predecessors, Cornelio convened an evidentiary hearing, which lasted several days.

Cornelius testified at the 2021 hearing that state and American Bar Association capital caseload guidelines are “basically ridiculous” and that he does not “pay any attention to them at all.” He testified that he “would never argue the things that you put in this write in any trial,” specifying that “raising the race card when it has no application to the case … would alienate any jury,” likely a reference to Prevost’s post-conviction attorneys describing Prevost’s early exposure to racial segregation and violence against Black people.

Cornelius also testified that he believed some of the mitigation evidence raised by Prevost’s post-conviction attorneys “cuts both ways” because if Prevost is “a cracked egg and he can’t be fixed, you’re probably going to have the death penalty on your hands.” He said he was not aware that trauma can cause cognitive deficits.

On Feb. 5, Cornelio issued her 158-page findings of fact and conclusions of law, finding that Prevost received ineffective assistance of counsel, citing their “failure to conduct a reasonable mitigation investigation.”

The judge concluded that Prevost’s trial lawyers did present evidence of his traumatic childhood, but failed to investigate and present to jurors evidence of his neurocognitive disorder, untreated major depressive disorder recurrent with psychotic features, and possible fetal alcohol spectrum.

“The jury missed out on hearing important evidence that [Prevost’s] inability to change his behavioral responses to a situation that is not working, including a relationship, is due to an organic brain impairment,” Cornelio wrote.

Benjamin Wolff, the OCFW director and one of Prevost’s current lawyers, praised Cornelio’s recommendation as an unusual assertion of judicial independence.

“We should all want judges to act as judges, and independently analyze the evidence and claims before them rather than robotically rubber stamp whatever the prosecution suggests. That’s what basic fairness demands,” Wolff said. “In the past, unfortunately it’s been rare for a judge in Harris County to both take the time to evaluate the evidence before her and draft her own findings of fact on that evidence.”

Last year, the Wren Collective, a group of former public defenders who do criminal justice research and policy, released a scathing two-part report on Harris County death row cases, describing the system as “utterly broken.” In nearly every case out of Harris County resulting in a death sentence over the previous 20 years, defense lawyers failed to find and present evidence that could have kept their clients off of death row, the report authors wrote.

One of the cases the Wren Collective looked at was Prevost’s. “At the punishment phase, his defense team told the jury that Mr. Prevost largely grew up in a loving and happy home,” the authors wrote.

“That was not true.”

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.