Democratic candidates in several key Senate races are breaking with a long-standing taboo among liberal voters: They’re increasingly embracing nuclear power as tech companies, banks and governments pour money into building new reactors to shore up a U.S. electrical grid that’s heaving under pressure from data centers, air conditioning and extreme weather.

Asked during last week’s televised debate against Republican Kari Lake what he would do to deal with Arizona’s rising temperatures, Ruben Gallego, the Democratic nominee for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat, pitched just one big solution: more nuclear power.

In Michigan’s final U.S. Senate debate this week, Democrat Elissa Slotkin listed nuclear reactors among the energy sources into which she said she wants to increase U.S. government investment.

In an interview with HuffPost on Wednesday, Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, the Miami-area Democrat challenging Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), called atomic power “a good first step in transitioning to greener energy and to lower the cost for Floridians in the state.”

“I would support nuclear,” she said.

Colin Allred, the Texas Democrat making a spirited challenge to Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), confirmed his support on Friday for building more reactors.

“Texas is a proud energy state, and in the Senate, I will always work to keep it that way,” he said in a statement to HuffPost. “That includes responsible oil and gas production, renewable energy like wind and solar, as well as nuclear power.”

In virtually every democracy among the 32 countries with nuclear power plants — including Canada, the Netherlands, and South Korea — left-of-center parties traditionally oppose atomic energy, while those on the political right generally support it.

For decades, the American partisan gap tracked this axiom. Democrats’ coalition historically included environmentalists eager to clamp down on uranium mining and radioactive waste, as well as anti-war activists who saw opposing nuclear power plants as a way to take a stand against atomic weapons. Republicans, on the other hand, generally championed a major U.S. industry seen as a key to the country’s economic development and technological competition with the Soviet Union.

When former President Barack Obama took office in 2009, 54% of Democratic voters favored the use of nuclear power, the highest level of support Gallup has recorded since the pollster’s biannual surveys started in 2001.

Despite that, the newly inaugurated Democrat elevated Gregory Jaczko to the top job at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, putting the agency — which is in charge of overseeing the world’s largest fleet of atomic power stations — in the hands of a skeptic who went on to call for a global reactor ban and refashion himself as a leading anti-nuclear activist.

Soon after Obama took office, his administration canceled the permanent nuclear waste repository long under construction at Nevada’s Yucca Mountain, an apparent concession to then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) that the federal government’s independent watchdog found was driven by political, not technical, issues.

Since federal law requires the U.S. to complete Yucca Mountain before considering alternative sites, blocking the project without advocating for legal reforms effectively froze the American debate over radioactive spent fuel. It also likely contributed to the industry malaise that saw more than a dozen reactors shut down and dozens more planned units abandoned over the next decade.

While the nuclear waste issue remained unresolved, the Obama administration soon started work on federal programs that laid the groundwork for the new reactor technologies now coming to market.

In 2010, Obama’s climate czar, Carol Browner, announced her support for nuclear power for the first time at an event organized by the center-left think tank Third Way. The administration then established the Department of Energy’s Gateway for Accelerated Innovation in Nuclear, a landmark program that helped give startups designing novel types of reactors access to national laboratories and other federal resources.

“It was the first time in a long time that a Democratic administration started to press the case that nuclear should be considered,” said Josh Freed, the senior vice president of energy and climate at Third Way.

It wasn’t long before another energy technology the Obama administration supported jeopardized the future of nuclear power. Hydraulic fracturing — the drilling technique known as “fracking” that uses pressurized water and chemicals to access previously unreachable deposits of hydrocarbons — took off, driving down the cost of natural gas and remaking the U.S. into one of the world’s top producers.

Since gas power plants were relatively inexpensive and quick to build, and the fuel to power them grew ever cheaper, nuclear projects could not compete. When it came time to renew power purchase agreements, buyers kept opting for deals with gas plants instead of renewing contracts with existing nuclear plants. That made maintaining nuclear plants too costly for utilities, prompting a cascade of shutdowns.

The 2011 Fukushima accident only soured investors on nuclear power even more. All but two planned reactors, a pair of units under construction at Georgia’s Plant Vogtle, were canceled.

While the Japanese government paid out compensation for just one death, an emergency worker who developed lung cancer years after the accident, scientists debate whether radiation exposure actually caused the illness. The forced evacuation of mostly elderly residents in the area, however, caused hundreds of deaths due to stress. In the years following the meltdown in Japan, the share of U.S. Democratic voters favoring nuclear power plunged as low as 34%.

Under former President Donald Trump, Congress passed bipartisan legislation to expand the Obama administration’s efforts to support next-generation reactor developers trying to commercialize technologies that, for example, use molten salt or high-temperature gas as a coolant instead of water.

By the time Gallup took its 2019 poll, support for nuclear energy began climbing again, reaching 46% in last year’s survey.

A Pew Research Center survey released in August found that nearly half of Democrats — 49% — backed an expansion of the existing nuclear fleet. By contrast, two-thirds of Republican-leaning and independent voters favored new reactors. But the 18-point partisan gap was the smallest in a list of energy sources that included solar panels, wind turbines, offshore oil and gas drilling, hydraulic fracturing or “fracking,” and coal mining.

Perhaps more notably, nuclear power represented the only source of energy with growing support among voters in both parties.

After President Joe Biden took office in 2021 with slim Democratic majorities in Congress, his party enacted two major infrastructure spending laws that directed billions of dollars toward researching and deploying new nuclear reactors and keeping existing plants open.

Just months after the Palisades nuclear plant in Michigan became the latest such facility to shut down over financial concerns, the Biden administration awarded the owners of California’s last atomic power station in Diablo Canyon $1.1 billion to keep the reactors running. Earlier this year, the Energy Department gave the owners of the Michigan plant $1.5 billion to reopen the facility, the first time in U.S. history a permanent closure is set to be reversed.

At the last United Nations climate summit, the White House led a pledge of more than a dozen countries vowing to triple global nuclear capacity by 2050. In September during the U.N. General Assembly, the world’s biggest banks announced their own pledge to begin financing nuclear projects again.

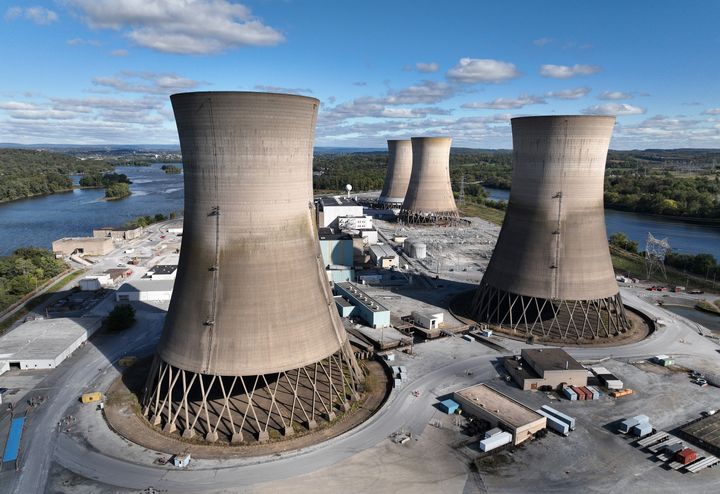

Big tech companies, meanwhile, are throwing deep-pocketed support behind reopening other nuclear plants and building new ones. Last month, Microsoft unveiled a $16 billion deal to reopen the defunct reactor at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania to help power its data centers as artificial intelligence ramps up the server farm’s appetite for electricity.

This week, Google and Amazon announced their own deals with reactor startups that came through the federal programs established over the past decade. The Jeff Bezos-founded retailer even made a direct investment into X-energy, the Maryland-based company building small reactors cooled with high-temperature gas.

“If they do get built, this week will actually be a week that is taught in history books,” Freed said. “It is when the era of nuclear energy changed from being speculative and focused primarily on innovation and getting liftoff to having momentum and being focused truly on scale and accelerated deployment.”

To help make those investments real, Biden signed legislation aimed at easing the permitting process for advanced reactors like those Google and Amazon want. The bill passed in the Senate 88–2. Sens. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) were the lone nay votes.

“It’s counterintuitive to what the casual observer’s perspective is, but the most transformative president for nuclear in the last 50 years is a Democrat who got the largest part of the nuclear agenda enacted with a full Democratic majority in Congress,” Freed said. “The reality of energy security, energy demand and climate change have dramatically changed people’s perspectives, including a lot of policymakers.”

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.