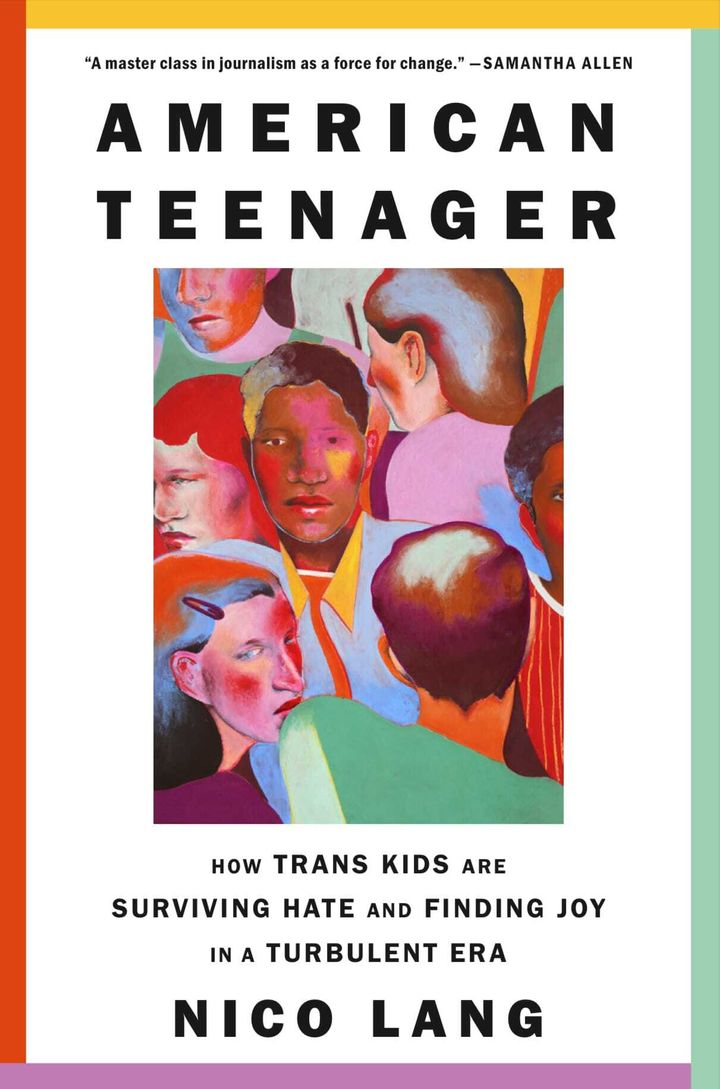

Below is an excerpt from ”American Teenager: How Trans Kids Are Surviving Hate and Finding Joy in a Turbulent Era,” a new book from LGBTQ+ journalist Nico Lang chronicling the everyday experiences of seven families of trans youth in seven states. In this chapter exclusively shared with HuffPost, a pair of trans siblings in Florida grapple with the impact of anti-trans legislation on their lives, while also navigating their own struggles. Some of the individuals in this excerpt are being identified by pseudonyms because they are concerned for their safety.

Today is Jack and Augie Darling’s second day in their new apartment, and absent a couch, they squat together on a purple suitcase in the mostly empty living room, alternating turns resting their heads on each other’s shoulders. Taking a hiatus from an afternoon’s worth of heaving boxes up a perilously narrow flight of stairs, the two engage in a bit of good-natured sibling rivalry — their favorite pastime — by comparing their respective double-jointedness. Dressed in black military boots and a matching black T-shirt featuring a skeleton wearing a top hat, Jack shows off her ability to bend her pinky all the way back to her wrist. Augie, peering out from behind the split-level bangs of their sixties shag haircut, responds by twisting their foot all the way behind them; the move, though, is as much a testament to the ballet classes in which Augie was once enrolled as it is the uncanny mysteries of biology.

Beside them is Van Helsing, a deceased betta fish named for the fictional monster hunter. Augie has been preserving the fish’s remains in a mason jar filled with alcohol solution because they couldn’t bear to bury him. “He’s keeping his color well, but his eyes are gone,” Jack says, drolly remarking that Augie has been carrying the frilly little corpse around for weeks. “It’s kind of creepy.”

As their U-Haul’s innards accumulate in the apartment, so do a series of random foodstuffs and objects indiscriminately scattered across the kitchen’s faux-marble countertops — a miscellany of microwavable ramen, boxes of whole kernel corn, a plastic container of Jif peanut butter, Gain detergent, and a skull ring gifted to Jack from a former coworker. Its previous owner claimed the heirloom was fused together from five hundred nickels, but the appraisal appears to be less than reliable: The same woman once boasted that she had shot her husband in the seventies and that he had it coming. “She was a pathological liar, so...” Jack says, experiencing a delayed realization of the ring’s sketchy provenance.

The most prized among Jack’s possessions have yet to arrive: The tank holding her turtle, Franklin, and her twin buckets of DVDs, mainly consisting of entries from the Criterion Collection of art house films. Her current favorite is 3 Women, an experimental film that unfolds with the misty logic of a half-remembered dream. Jack likes the movie so much, she says, because she has no idea what it’s about, so she comes away with a new theory each time.

The day’s major focus is getting Jack and Augie’s mattresses moved into their respective bedrooms, but their mutual laboring in the thick heat of Pensacola, Florida is a reminder of all that has yet to be acquired. They still don’t have towels, trash cans, shower curtains, ice trays, or even a bed for their mother, June, who slept the previous evening on a bedsheet spread across the carpeted floor. When June fires up a frozen veggie pizza for the hungry crew, she uses its flattened box as a tray and a bath towel as an oven mitt; our feast is served on paper plates from the nearest Target store.

The family’s lack is a byproduct of everything it took to get where they are now: They spent two months homeless and living in Airbnbs as June begged relatives, her classmates at college, and even total strangers for enough money to house them. The displacement was extremely abrupt, following a blowout fight with her former boyfriend after June naïvely brought up the idea of buying Jack a car for her nineteenth birthday. The unexpectedly heated discussion ended in an argument over policies pushed by Governor Ron DeSantis (R) targeting transgender children, which was then followed by demands that June and her children vacate. Overlooking the balance of negative six dollars in her checking account, June’s ex offered to let her use his car — for seventy-five dollars a day — to find somewhere else to live.

June, a Navy veteran, is finishing her master’s degree in occupational therapy and couldn’t afford the security deposit on a new place, so Jack paid it to ensure they had consistent shelter and weren’t forced out onto the street. With the wages she had earned from working at the retail chains Goodwill and Dollar General, Jack also rented the U-Haul and gave June money to buy groceries, but the still-escalating expenses have left Jack with little else to give. She has just three hundred dollars remaining in her savings, down from three thousand when they first became unhoused.

The financial and psychological stressors of homelessness have only added to Jack’s ever-growing list of resentments, which are aimed at both her parents and the state where she has lived for most of her life. She is angry at June for poor decisions that she feels have contributed to their displacement but also feels increasingly trapped and alone in Florida, as lawmakers further intensify the Darlings’ already overwhelming problems. Just twenty-four hours after Jack is able to sleep in her own bed again, Governor DeSantis will sign a law that bans transgender minors from receiving treatments like hormone therapy and puberty suppressors. The law will add additional restrictions for adults seeking gender-affirming health care: It prohibits trans-affirming medications from being prescribed through telehealth appointments or by a nurse practitioner, which is how the vast majority of transgender people in Florida get their prescriptions.

The situation is sadly familiar for Jack, who already lost her health care once because of Florida’s regulation. Although the state wouldn’t ban transition coverage through its Medicaid program until August 2022, a miscommunication with Jack’s former medical provider — who no longer practices in Florida — led the Darlings to believe that it had been revoked well before that decision was officially made. The last of Jack’s estrogen ran out in November 2021, and she found a new medical provider the following April, in time for her eighteenth birthday. Over those five months, she watched her femininity become something she no longer recognized, comparing the transformation in her flesh to the oeuvre of body horror maestro David Cronenberg. “For me, it didn’t feel like changing back into a man — it felt like turning into something inhuman,” she tells me after the law is signed, upon getting an email from her telehealth provider explaining that they can no longer treat her.

During the time that Jack spent without estrogen, she barely left the dark of her room because she didn’t want anyone to see her. The feeling was mutual: She didn’t want to see herself, either. “The amount of willpower that it takes to have to wake up every morning and think, ‘OK, what changed now?’ You watch your body that you were so happy with deteriorate, and you don’t know if it’ll ever come back the same way.” That period of her life has scarred her irreparably, and she worries for all the transgender kids who will suffer the same ordeal under Florida’s new regulations.

Jack isn’t out to anyone but close friends and family members she trusts, and when her medication was taken away from her, she began carrying around an electric razor in fear of her facial hair growing in; she particularly dreaded the sight of the frightful down sprouting from the edge of her chin. On HRT, she only had to shave once every three days to get by, but off it, she started timing when she would need to excuse herself to the bathroom. Terrified that a voice crack would unintentionally out her, she would take a drink before speaking to warm up her vocal cords. She was constantly second-guessing herself — afraid that she had missed something, that one slip-up could jeopardize the safe cocoon she had worked for years to build — and knowing that her own elected lawmakers were responsible for her torment only made it so much worse. “Like any teenager, you don’t think people understand you,” she says, “but it was taken to such an extreme, where the government doesn’t understand you so much that they want you eradicated.”

Jack knows that their new apartment should represent a fresh start, an opportunity to begin again in a place where she can finally decorate the walls, hanging posters of the cyberpunk anime Ghost in the Shell and The Walking Dead television series, but it’s hard to feel much of anything. She spends most days on the enclosed balcony dangling a cigarette as she vacantly stares into the expanse of the parking lot, wondering if the girl she was prior to her forced detransition will ever come back.

When she came out at fifteen, Jack took her first steps into womanhood by borrowing her mother’s sale-rack bohemian threads — floral dresses, mesh crop tops, tattered jean shorts — before transitioning to her now-trademark monochromatic wardrobe. Until recently, Jack’s only item of clothing that wasn’t solid black had been a sweater covered in teensy cartoon demons, which she finally surrendered to Augie because she had rarely ever worn it. While Jack saw a distinct utility in wearing one color all the time, the goth metamorphosis was also inspired by fictional characters she admired: the chain-smoking Marla Singer of the misunderstood fascism parody Fight Club, the hacking avenger Lisbeth Salander of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium novels, and other feminine outsiders whom she felt simultaneously projected confidence and a defiant unknowability. But behind the pop culture homage of her dyed black hair, labret piercing, and shaved eyebrows, a part of Jack is struggling with her identity; she wonders who she is after so much has been taken from her and who she will become now that she survived it.

What concerns her family is that Jack no longer dreams of the future the way she used to. She’s hesitant to discuss her goals and ambitions — both professionally and personally — and her loved ones worry that she’s lost sight of her life beyond the horizon of now. June is the family’s inveterate idealist, constantly repeating everything is going to be OK to herself until her hands physically shake, but Jack, on the other hand, can’t muster up the energy to do more than just last another day. “I feel like too much optimism has plagued so much of my life,” she tells me as the balcony’s dutiful ceiling fan soundlessly whirls, curling a gale of smoke around us. “I’d just rather not think about a future or a past.” She and her best friend used to fantasize about running away together to Portland, Maine, where they would live in a lighthouse on the cliffs and stroll along rock beaches, arms linked conspiratorially.

But if the past has taught her anything, Jack believes, it’s that she can’t rely on anyone but herself. She has strongly considered the possibility of disappearing altogether: changing her name, getting new bank cards, and cutting off all ties with family and friends, even those she holds dearest. It’s been so long since she was happy, she says, that she almost doesn’t remember what it was like. “I’m not cripplingly depressed all the time,” she says. “I’m just so disconnected from everything that I don’t really care about anything.”

Jack will spend the duration of my time in Florida searching for reasons to resume her regularly scheduled life, signs that the imminence of possibility is something she can still feel. As much as she thinks she doesn’t need other people, she will find glimpses of the renewal she seeks in a family member who also knows what it is like to feel so chillingly alone in the world that it seems impossible anything could ever be different: her younger sibling, Augie.

A sixteen-year-old high school sophomore, Augie picked a tremendously unlucky time in Florida’s history to come out as nonbinary. In February of this year, they told their mother in the parking lot of a Walmart, “I’m not a chick, but I’m not a dude either,” choosing the big box chain to unburden themselves because they’d seen other kids come out in parking lots on social media. The very next month, Florida’s Boards of Medicine and Osteopathic Medicine finalized rules expanding the ban on transgender care to all minors who receive gender-affirming care in the state, not just Medicaid recipients. That decision effectively made Governor DeSantis’s transgender health care ban a moot point before it was ever signed, but he continued to up the ante anyway, eyeing a then-widely presumed presidential bid. This week’s raft of newly signed legislation included bills limiting the public restrooms that transgender people are permitted to use and making it a misdemeanor for drag artists to perform in view of minors.

Because they can’t always rely on the adults around them — whether their state’s political leadership or those entrusted with their care — Jack and Augie have learned to lean on each other for support, to show each other the way forward. Before they even had the words to describe their relationship to gender, they were each other’s best allies. Jack would swap her monster trucks for Augie’s Barbie dolls the moment their biological father — with whom they no longer have a real relationship — left the room. When Jack found a pair of plastic cockroaches on the sidewalk last year, she made them into earrings to give to Augie as a present, and Augie now wears them all the time.

The siblings love, quarrel, and tease like family, never afraid to weaponize an embarrassing anecdote to get a rise out of the other, such as the time that Jack says Augie “ripped the fattest fart” after drinking too much kombucha before going to the theater to see “The Lego Batman Movie.” “You had to pick the quietest moment,” Jack recalls of seeing the animated meta-superhero comedy. “Everyone knew it was you.” Legs akimbo on their newly situated mattress, Augie explains that they were attempting to time the fart’s release to a dramatic moment in the film but woefully miscalculated the big drop: “I thought something big was going to happen, and then nothing happened.”

Jack and Augie have braved so much together. In addition to surviving homelessness and Jack’s medical trauma, they spent the early years of their respective adolescences watching their biological father repeatedly abuse their mother, a years-long torrent of terrors from which June is still healing. But in truth, they have endured because of the special relationship that guided them through the bleakest of hours — having someone in the next room to play video games with, to hate the world with, to know that one person understands what they are feeling. During the months that Jack spent without her medication, it was Augie who kept their big sister from succumbing to the gloom, knowing that life would be sadder and lonelier if they didn’t have each other. “I would probably be a shell of a person,” Augie says. “We go to each other and complain about how stupid this situation is. We can just be mad about it together, be broody and angry.”

Jack comes very close to giving into earnestness, to confessing just how much it has meant to her to have someone who sees her for exactly who she is, but at the last second, a glint flitters across her eyes; she has chosen violence instead. She says, with a too-rare smile: “You’d be so boring without me.”

Excerpted from “American Teenager: How Trans Kids Are Surviving Hate and Finding Joy in a Turbulent Era” by Nico Lang. Copyright © 2024 by Nico Lang. Published and reprinted by permission of Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.