The conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court appeared ready to overturn another major decades-old precedent when it heard arguments on Wednesday in two cases about fishing regulations.

The cases — Relentless Inc. v. Department of Commerce and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo — challenged regulations imposed by the National Marine Fisheries Service in 2020 that require fishing boats to pay the salary of the federal inspectors who ride on their boats. But the family-owned fishing companies challenging those regulations made a much broader argument: that the court should overturn its own 40-year-old precedent in the case Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council and rule that no federal agency can issue any regulation without specific authorization from Congress. That case’s precedent, the lawyers argued, was out of date and no longer necessary.

If the court overturns its ruling in Chevron, agencies would be more reticent to issue regulations where laws passed by Congress are ambiguous. It would also open the door to a flood of litigation over existing regulations. And since Congress lacks the institutional capacity and the calendar space to pass legislation authorizing every agency rule and regulation written under ambiguous legislative language, the courts would be the final arbiter on each regulatory decision.

In recent years, conservative justices have made clear their hostility to the Chevron decision. The Supreme Court has largely stopped using it in administrative law cases, instead relying on newer judicial canons to strike down federal regulations, like the “major questions doctrine” in the 2022 case of West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, which assumes that Congress does not delegate authority to agencies to make decisions on major issues. But what was most telling about the cases was how explicit the lawyers for Relentless and Loper Bright were in explaining the partisan and ideological motivations for their arguments.

For decades, the Chevron ruling provided a legal framework for how courts should defer to a government agency’s interpretation or enactment of a regulation: If Congress hadn’t clearly stated an interpretation in the statute, the precedent goes, then the federal court should allow the agency’s decision to stand unless the regulation represented an unreasonable interpretation of the underlying law.

The Chevron precedent emerged after then-EPA Administrator Anne Gorsuch, the mother of Justice Neil Gorsuch, issued new rules in 1981 that reduced the Clean Air Act’s regulation of pollution at power plants. The Natural Resources Defense Council challenged the new regulations, and the U.S. Appeals Court for the District of Columbia Circuit, in a decision written by Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg, struck them down. In a 6-0 decision in 1984, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed Ginsburg’s ruling and created the framework for judicial review of federal agency regulations.

Conservative judges don’t tend to like granting the federal government more regulatory power, but the rules at the heart of the Chevron case were actually deregulatory.

President Ronald Reagan had just won a smashing victory in 1980, and Republicans had won three of the last four presidential elections (and would go on to win the next two). Meanwhile, the judiciary, particularly the D.C. Circuit, was still dominated by liberals. The conservative embrace of the Chevron decision was intended to enable Reagan’s deregulatory agenda and to squash the liberal D.C. Circuit. It’s no surprise, then, that the late Justice Antonin Scalia was a staunch defender of it.

But times change. As of 2024, Republicans have lost the popular vote in eight out of the last nine presidential elections, leaving federal agencies largely led by Democratic appointees. But in the courts, increasingly helmed by Republican-appointed justices, conservative modes of legal interpretation — textualism and originalism — have taken center stage. The result could be a rollback of agencies’ ability to interpret their own statutory authority to enact regulations — in this case, the progressive policies supported by the Biden administration.

In questioning Paul Clement, lawyer for Loper Bright and a conservative legal luminary, Justice Samuel Alito asked why he thought Chevron was “initially popular.”

“Were [the justices] wrong then, and if they weren’t wrong, then what, if anything, has changed since then?” Alito asked.

“I think they were partially right then,” Clement replied, adding that, he reasoned, “Chevron was a response to some of the excesses of the D.C. Circuit in the freewheeling ways of the late ’70s and the use of legislative history.”

“We now, I think, are all textualists,” Clement added.

Alito posed a similar question to Roman Martinez, the lawyer for Relentless.

“Would you agree that one of the reasons why Chevron was originally so popular was concern that judges were allowing their policy views consciously or unconsciously to influence their interpretation of the statutes?” Alito asked. When Martinez replied he did agree, Alito asked why he thought that concern was unfounded.

The “fear” of judge’s policy views slipping into their decisions “has diminished over time,” Martinez said, because of the “very salutary developments in the way” federal judges have adopted conservative modes of legal interpretation.

Previously the courts relied on “legislative history” and “more freeform analysis” that, according to Martinez, “made it easier for policy considerations to infect the judicial decision making process.”

“But this court has made clear that really we should be text-focused,” Martinez said.

These are, ultimately, arguments about the changing ideological makeup of the court, particularly its rightward swing since the Trump administration’s appointments.

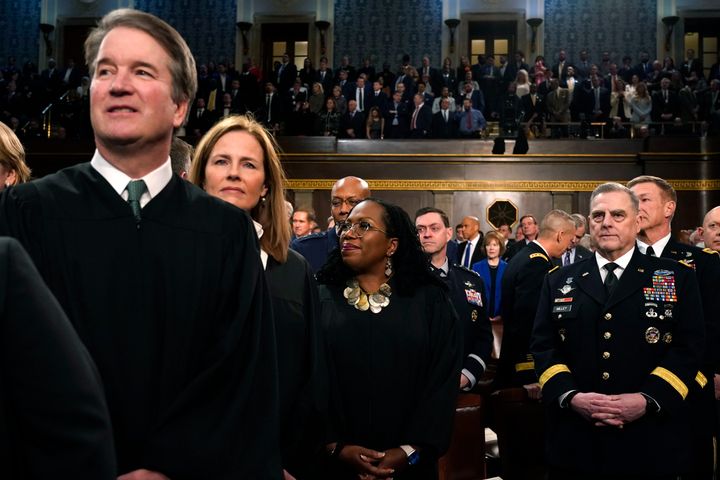

Justice Brett Kavanaugh took another angle in his questioning, arguing that federal agencies’ change of leadership with each new presidential administration means those agencies are too unstable to make rules.

“The reality of how this works is Chevron itself ushers in shocks to the system every four to eight years, when a new administration comes in, whether it’s communications law or securities law or competition law or environmental law,” Kavanaugh said.

He added, “It just seems like you just pay attention to when a new administration comes in at EPA, at SEC, at FCC, you name it, it’s just massive change. That is at war with reliance.”

This reasoning came under withering assault from the liberal justices, in particular Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, during questioning of Relentless’s laywer.

The “shocks to the system” that Kavanaugh described as resulting from policy changes made when a new administration takes office are really the reflection of “democratic structure,” Jackson argued.

“We have the new administration being elected by the people on the basis of certain policy determinations,” she said.

“I guess my concern is that judicial policymaking is very stable, but precisely because we are not accountable to the people and have lifetime appointments,” Jackson continued. “So, if we have gaps and ambiguities in statutes and the judiciary is coming in to fill them, I suppose we would have something of a separation of powers concern related to judicial policy making.”

The elimination of the Chevron precedent could enable judges to insert their policy judgments in the guise of law over decisions made by policymakers in the federal bureaucracy, according to Jackson. If allowed to have that much sway, judges could effectively veto or approve policies governing everything from limits on greenhouse gas emissions to antitrust law.

“Doesn’t the court have to not only police the other branches, but itself as well?” Jackson said.

It did not appear that the conservatives were amenable to any arguments of judicial overreach. Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Alito were explicitly hostile to Chevron in their questioning of the fishing companies’ lawyers, and the other three conservatives, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett, did not appear inclined to side with the liberals.

The court heard separate arguments in the two cases, despite their similarities, because Jackson recused herself from the Loper Bright arguments. She had previously served on a D.C. Circuit panel that heard arguments on the case before she was appointed to the Supreme Court.

A ruling on the two cases is expected before the end of June.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.