It was freezing cold in Texas in February 2023, and the ice and snow basically had me barricaded in my new solo apartment. When my dad called to see how I was holding up, I told him I was fine, but my shaky voice probably gave me away.

It was my first time living alone, and the ice storm made it glaringly obvious to me and just about everyone how lonely I was. I spent my days working from home and my nights scrolling my phone. There were no roommates to bother and no parents to bother even more. My apartment was constantly quiet, and I was bored. It was just me and the dog, who I was starting to think was never going to learn how to speak English. So once the ice melted, my dad bought me a $200 Samsung TV.

My mom told me that my TV had its own streaming service and there was a channel that played “That Girl” 24/7. I had never seen “That Girl,” which ran from 1966 to 1971, but my mom’s explanation that it was “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” before “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” intrigued me.

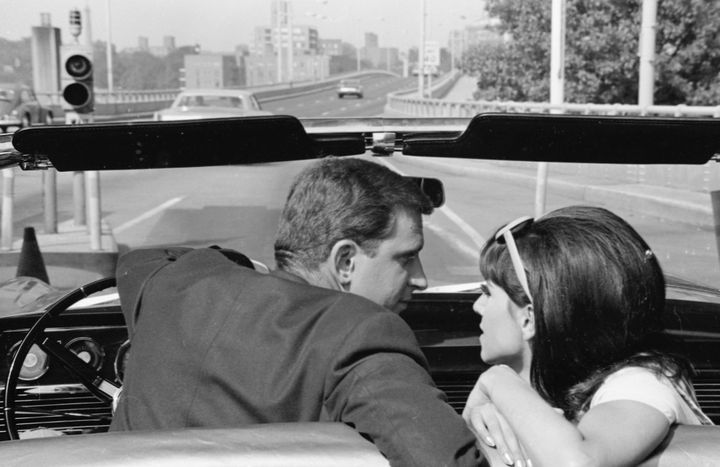

After a few episodes, I became obsessed. In “That Girl,” Ann Marie (Marlo Thomas) is an unmarried woman living in New York City, hustling multiple jobs trying to “make it” in her career while her overprotective parents and supportive boyfriend, Donald (Ted Bessell), cheer her on. I related to Ann, minus the boyfriend, because she was like me in a lot of ways: creative, funny, scatter-brained at times. She was also the kind of girl I wanted to be — bubbly, beautiful, 103 pounds, happy. Antidepressants probably weren’t even in Ann’s vocabulary much less her medicine cabinet.

I started watching the show nonstop. I could turn the “That Girl” channel on at any time of the day to watch one of the 136 episodes from the five-season series. While I worked from home, Ann was with me. She auditioned for acting jobs while I wrote breaking news stories. Ann spent evenings with her parents while I did the same. Ann made dinner for her boyfriend, and I dreamed about doing the same for my own Donald one day.

“That Girl” was groundbreaking because it was one of the first sitcoms centered on an independent single woman. Before that there were housewives June Cleaver and Lucy Ricardo, or fantasy women like Jeannie in “I Dream of Jeannie” or Samantha in “Bewitched.” Ann Marie wasn’t a housewife; she wasn’t just someone’s daughter; she wasn’t just someone’s someone. She stood on her own, and the show revolved around her stories. I’m not naive enough to think that life in the 1960s was simpler or easier, but “That Girl” provided me an escape. Though my problems couldn’t be solved in 30 minutes, Ann Marie’s could. The show premiered more than 50 years ago, but Ann dealt with some of the same issues that I face today — hardships of chasing a dream career, women’s rights, an overprotective father and many others. I saw myself in Ann.

I started to miss Ann and Donald when I was away from them too long, which sounds just as insane as it is. If I went out to lunch or to go shopping, I couldn’t wait to get home to see what they were doing.

I started researching the origins of the show. I shopped online for any “That Girl” memorabilia so I could decorate my apartment. I incessantly told my friends about Ann and Donald as if they were a part of my life. No matter how many times I rewatched the same episodes, I never got sick of them.

“You won’t believe what Donald did today,” I texted a friend.

“Oh, my god, Ann owes $2,000 in taxes just like me,” I posted on social media.

“Donald is going to propose to Ann at 7:30 tonight,” I texted my dad.

“Again?” he responded.

Then for my 33rd birthday, I threw myself a “That Girl”-themed party where I made all my friends dress up in 1960s glitz and glam. While we ate and drank, “That Girl” played on the TV in the background, and I made everyone listen to me while I explained how “That Girl” was a trailblazing show.

One of my favorite scenes is from an episode in Season 1, when Ann Marie’s dad, Lew (Lew Parker), takes her out to dinner for her birthday. It’s never mentioned how old Ann is turning, but she’s old enough to live on her own and still young enough to be seen as a girl. After dinner, Ann’s dad drops her off at the door to her very own apartment but not before Ann asks him a question. She wants to know if he was “terribly disappointed” on the day she was born when he found out his new baby was a girl.

Lew Marie gives a sweet, short monologue and reassures her that when he heard his new baby was a girl, he simply thanked God.

“Let me put it this way: If there was a factory where I could’ve ordered my own specifications, you would’ve been what I ordered, even with all your craziness,” Lew Marie tells Ann.

I had watched that scene dozens of times, and it always made me tear up. To me, Ann’s question was less about her gender and more about if she had lived up to his expectations. It perfectly summarizes what it feels like to be a child, a daughter, a girl and a woman coming into her own. As she is celebrating her ageless birthday, she wants to hear from her dad that she’s enough.

Less than a month after my birthday party, I woke up and rolled over to turn on the TV to see what Ann and Donald were up to. But the screen was black. Channel 1322 was no more. Samsung had taken “That Girl” off its streaming service.

I cried off and on that day. I texted my dad to “fix it,” thinking maybe because he installed the TV, he knew how to get this channel back on air. My mental health took a nosedive. My apartment was back to being quiet and lonely.

So I tried other shows. “Family Ties” wasn’t the right fit, maybe because Alex P. Keaton was no match after falling in love with Donald Hollinger. My friends suggested “Girls,” the Lena Dunham-created show that is probably the closest to a modern-day version of “That Girl.” But while Ann in “That Girl” was a woman I aspired to be, Hannah in “Girls” was neurotic, self-absorbed and a struggling writer.

“I didn’t want to watch myself on screen,” I told my friends. TV was meant to be an escape.

No one could quite understand what I was feeling. I was sad. It felt like I had lost a friend. And then I was mad. How could the channel be gone? “That Girl” was what I watched for 10-plus hours a day, and without the show, I started to miss Ann and Donald. I would often wonder what they would be doing if I could watch them. With nobody to understand the profound sadness I was feeling, I did the only thing I could think to do. I called Marlo Thomas, the woman who made Ann Marie and “That Girl” famous, to talk about the show.

From her home office, Thomas chatted with me over Zoom. I could see her Golden Globes in the background, one of which she won in 1967 for “That Girl.” She told me about getting the show on the air nearly 60 years ago. The show was her idea, but network execs wanted Ann to be someone’s daughter or wife or niece, but Thomas wanted Ann to be enough on her own.

“The network wanted me to live with my aunt,” Thomas told me. “Or they wanted my little 6-year-old brother to move in with me. And I said, ‘No girl goes to the big city and lives with her aunt. And that’s not the point. The point is to be independent.’”

She also fought them again when they wanted the series to end with a wedding between her and Donald.

“I said, ‘I would be betraying all my girls and women who watch the show. We can’t say that the only happy ending is a marriage; that would be the worst thing to say,’” Thomas told me. “I said, ‘Well, that’s no longer ‘That Girl.’ That’s another show. You can’t call it ‘That Girl.’ That will be called ‘That Married Couple.’”

So instead the series finale is an episode where Ann takes Donald to a women’s liberation meeting. It’s anticlimactic and perfect.

I told her how Lew reminded me of my dad. When Ann has to fly from New York to Miami for work in a Season 3 episode, she walks on the plane to find out her dad is joining her. My dad has accompanied me on plenty of outings, but when he couldn’t do that, he tracked my location to make sure I made it safely from the airport to my hotel.

Lew was tough on Ann but loved her greatly, just like my dad.

Thomas shared that sentiment, telling me that Lew was based on her late father, actor and producer Danny Thomas.

“My dad was very strict,” Thomas told me. “And he would wait up for me. Sometimes he’d be out on the lawn waiting up for me. He was just very strict, but he was completely loving. I’m a true daddy’s girl. You could see how much Ann Marie loved her daddy and how much he loved her.”

And then she brought up my favorite scene unprompted.

“When we did that scene, [Lew Parker] couldn’t get through it without crying,” Thomas told me. “He didn’t have any children. He’d been married two or three times. But he didn’t have children. And so I became like a real daughter to him. And so when he had to say that speech about how he loved me from the moment he saw me, however, when he couldn’t do it, he just kept crying. We started over and over and over. And then finally I grabbed his hand and he did it.”

Thomas told me she wanted to make sure she spoke about Ted Bessell, the actor who played Ann’s boyfriend, Donald. That was an easy topic of conversation because I had fallen in love with Donald while watching the show. I told Thomas how much I appreciated that Donald never added stress to Ann’s life. His role on the show was to help Ann and cheer her on. In one episode, when Ann is featured on the cover of a magazine, Donald goes and buys every copy at the corner bodega.

Thomas told me that Bessell was like that in real life. When Thomas would argue with the network over the phone about a storyline in “That Girl,” Thomas said that Bessell was usually in the room rooting her on.

“I’d be on the phone arguing about something that they didn’t want me to do,” Thomas told me, recalling moments in the makeup room with Bessell supporting her ideas. “He was just always on my side, just always there. He was just on my side, and that’s why I think you saw so much love between us.”

Since discovering “That Girl,” I’ve asked several women older than me if they watched it when it was on TV, and the answer is always yes. I asked Thomas if she thought a 33-year-old woman like me would be completely enamored by the show nearly 60 years later.

“No, you know, it was so hard to get it on,” she told me. “Because there had never been a single girl on television before that didn’t live with her family.

“Getting past those barriers really was a long race, jumping over obstacles to do the show that we wanted to do. So I wasn’t even thinking about the next year, let alone years ahead. I just wanted to get that show on. And it was very hard. It’s exciting to be the first, and it’s really hard to be the first at anything because you have to break through membranes of myth. People don’t want to see a girl without a family; people aren’t interested in a girl who doesn’t want to get married.”

I think often about Thomas as a young woman fighting network executives. A young woman creating a show now still seems like a big deal, so it’s hard for me to imagine what the male executives thought of Thomas during those 1960s board meetings. She said that usually she would be the only woman in meetings about the show.

“The secretaries would come in and bring coffee, and it always used to aggravate me so much. I would stand up, go get my own coffee,” she said. “And it just bothered me that everybody else was a man in a suit and a tie.”

I knew Thomas was ahead of her time before I spoke to her, but hearing her tell me about it put it into perspective because she’s still ahead of her time. She told me about her work with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the hospital her dad founded in 1962, for which she now serves as the national outreach coordinator. She told me the hospital is constantly working on adding new equipment to help save the lives of sick children. I was touched not only by her care for sick children but also by her work carrying out her late father’s vision to make sure children don’t die young.

And then there’s the children’s album “Free to Be ... You and Me,” something she produced in 1972 after she became an aunt and noticed that there were no kids’ books that challenged gender norms.

“We did a song called ‘William Wants a Doll’ and another song, ‘It’s All Right to Cry,’ and that was in 1972, and so many gay men have come up to me and said, ‘I just knew when I heard those songs, it was going to be OK. I was gonna be OK.’ It just makes me cry. That’s what entertainment can do. That’s what’s so exciting about being creative.”

I told her that at 33, all of my friends are already married and starting their own families, so it means a lot to me that she didn’t get married until she was 42. She also never had children of her own, instead helping raise husband Phil Donahue’s children from a previous marriage.

It’s been three months since the 24/7 channel with “That Girl” was taken off the air, and since then I’ve found comfort in other things, like going on walks with my dog or watching trashy reality TV that sets feminism back 100 years — something I couldn’t bear to tell Thomas about.

I’ve had to mourn the disappearance of “That Girl,” but my conversation with Thomas comforts me more than the show ever could. She urged me to pick up where she and Ann left off and create my own story.

“The most important thing you can do in your life is do what you feel,” Thomas said. “You got, I don’t know, 80 years ahead of you to figure out what else you want to create, to notice, to point your finger towards, hey, look at this. This is something we should be talking about, or this is something we should remember. I’m gratified that you at 33 see the importance of ‘That Girl.’ That means so much to me.”

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.