To hear some adults tell it, adolescents are exposed to troubling and inappropriate messages found in many children’s and young adult books, TV, and film. But one look at the staggering (and growing) list of banned books will give you a sense of what those messages are:

1982’s “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker, a sprawling novel about a queer Black girl who overcomes decades-long physical and sexual abuse through the love and support of Black women. 2019’s “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe, an illustrated story of a young protagonist exploring their identity outside the binary. 2009’s “Tricks” by Ellen Hopkins, the tale of a group of teenagers who fall prey to drug use and turn to sex work. 2017’s “Dear Martin” by Nic Stone, the story of a Black teenage boy who’s wrongfully arrested and grapples with racial injustice and Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy. 2006’s “Sold” by Patricia McCormack, a story about a young girl who is sold into slavery in India.

These narratives are not completely unrelated to many young readers’ real-life experiences — and a quick glance at the news or reading the words of young people themselves could confirm that.

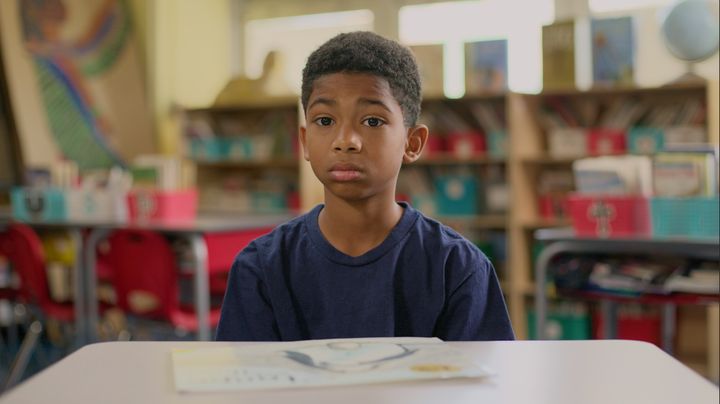

In “The ABCs of Book Banning,” the Oscar-nominated short documentary from directors Sheila Nevins, Trish Adlesic and Nazenet Habtezghi, young people reveal their frustrations with the draconian concept of restricting their access to literature.

The argument from the adult side has often been that book bans, or rulings like the British Board of Film Classification’s recent decision to increase the rating of the 1964 family film “Mary Poppins″ from “U” for Universal to PG due to “discriminatory language,” are necessary to protect kids.

But are either of these tactics effective in a world where many adults, including some parents and politicians like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, want to restrict knowledge of some aspects of history entirely?

As evident in “The ABCs of Book Banning,” children are more aware of — and, in many cases, more directly impacted by — the world around them than they’re given credit for. Racial profiling, gender identity and LGBTQ rights are all themes of which they are already painfully aware.

The film makes it increasingly clear that many children and teens can actually handle conversations about these topics. Some adults, though, are unwilling to have them, whether a movie comes with a “parental guidance” suggestion or not.

Opponents of the bans, like teachers and authors, have railed against them, fearing they serve to limit the facts from young people and “control the narrative.”

In February, the Washington Post reported that managers of an Asheville, North Carolina, bookstore took in eight tons of picture books restricted by the laws in Florida, which has the highest number of banned books in the U.S. They also managed to send some books to people in the Sunshine State who requested them.

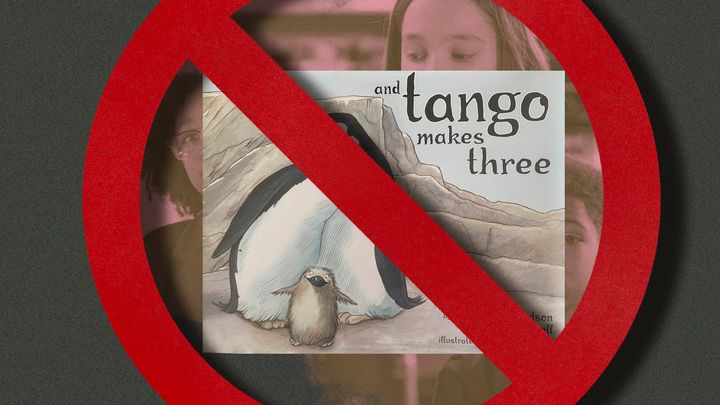

In “The ABCs of Book Banning,” Ridley, a 9-year-old student in Jacksonville, struggles to understand the decision to ban “And Tango Makes Three,” Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell’s 2005 illustrated book about two male penguins who welcome a child through another penguin’s egg.

“It’s about two penguins that are gay with each other and, even though they have their differences from the other penguins, they could still have a child, take care of it,” Ridley said. “They could do pretty much everything but lay an egg. They’re still human.”

What’s especially critical here is that Ridley is able to note the universality and humanity of an illustrated story that centers animals.

“Everyone deserves these beautiful books; to read, to learn, etcetera,” Ridley continues. “They teach them about culture, what they can be. They should be able to be what they want to be. But they can’t be without knowing what it means.”

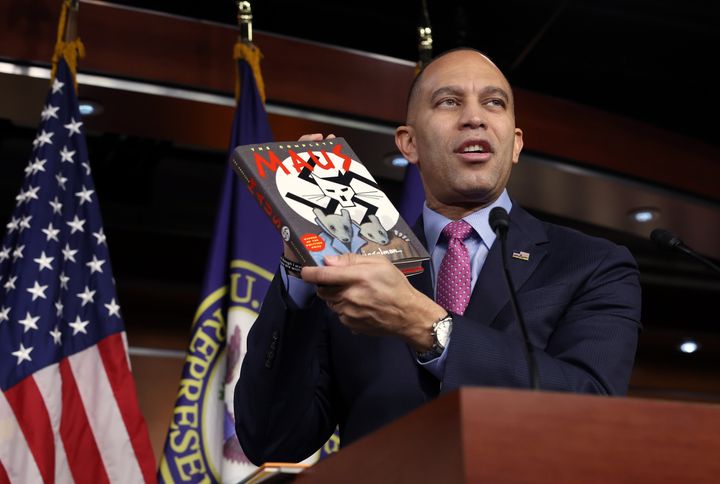

Kierran, 15, reckons with what it means to ban author Art Spiegelman’s 1986 graphic novel, “Maus,” detailing a character’s experience in the Holocaust.

“I feel like if you’re trying to ban this book, you’re trying to ban Jewish history,” Kierran says plainly. “That’s like saying, ‘Well, this didn’t happen,’ which will probably just eventually lead to the same thing happening again because people don’t know it even happened in the first place.”

Then the teen gets right to the meat of the issue: “Because you’re stealing knowledge. Why would you want to steal knowledge?”

Kierran’s final question, to which there’s no response, lingers long after the film ends. If adolescents are able to properly discern queer themes, concentration camps and the potential of history repeating itself, they might be open to a dialogue around why, say, “hottentots” is a prejudicial term.

That’s the word young “Mary Poppins” viewers encounter twice in the Disney film, and for a long time it was deemed entirely acceptable by a racist white Hollywood. It’s a racial slur historically targeting the Khoekhoe, an Indigenous people from South Africa. The word is uttered by Admiral Boom (Reginald Owen), a supporting character.

To be fair, the movie’s increased rating is deserved. It also creates a vital opportunity for adults to talk to young people about why the term is so harmful.

Leshu Torchin, a senior lecturer of film studies at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, recently told The New York Times that the new rating indicates that “children could watch a film, and if not with their parents to help contextualize things, could come away either thinking certain language is OK, or come away from it feeling harmed by what they’ve just seen.”

That makes sense, in theory. But considering many adults’ efforts to outright restrict children and teens from learning history (or even present-day events) as depicted accurately in books, it’s hard to feel confident that those conversations will happen in many homes.

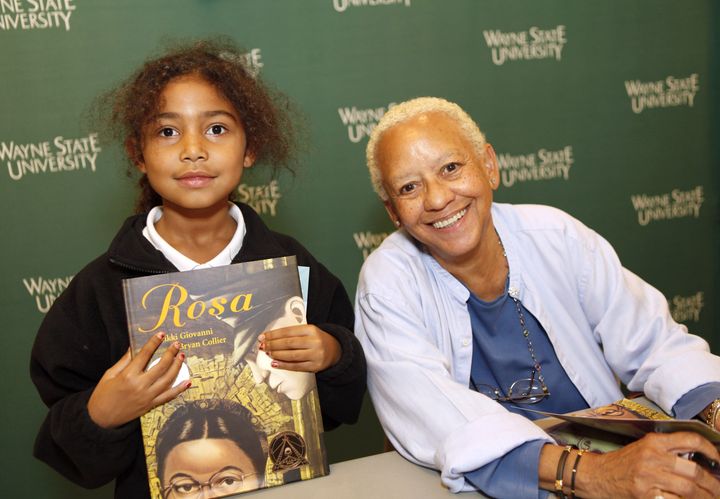

Poet and author Nikki Giovanni, who appears in “The ABCs of Book Banning,” believes no book or hateful term should be restricted at all. That includes her own, 2005’s “Rosa,” a children’s picture book about activist Rosa Parks that has been subject to bans.

“To ban it is to give it power over you,” she says. “There’s no word that should have power over you. If it’s a word, you can use it. Everyone may not like it. Everybody may not want to hear it. But you can’t give a word a power. Words have to be free.”

Giovanni then puts the onus on the consumers: “We’re the ones that have to decide what to do with the words that we’re hearing and the words that we’re saying.”

There’s woefully been no consensus around what that decision should be.

It feels like every year now in our evolving social climate adults keep bumping into new ways to contend with or simply erase these issues, particularly when it comes to art for kids and teens. In 2021, Disney+ made the conscious choice to add a disclaimer to 18 episodes of “The Muppet Show” that contain culturally insensitive images.

So the streamer maintains the episodes and its TV-G rating that suggests it’s suitable for all audiences, but encourages essential dialogue for educational purposes. Part of that warning reads as follows: “Rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together.”

That seems more effective, assuming adults go on to have those conversations, than, say, revising inappropriate text and imagery, as the late Roald Dahl’s estate did with his children’s books just last year.

As Kierran said, attempts to erase history are counterproductive. You can confront it, discuss it and try to prevent it from happening again. Because what’s to stop kids from learning and using offensive terms on their own if 1) they don’t know they’re offensive or 2) don’t understand their historical context?

And what message does it send to kids when many books that are considered problematic — among a staggering 3,362 cases, according to PEN America last year — are usually ones that don’t center white, cisgender, and/or straight characters and storylines? Their themes might be uncomfortable for some. But that’s not the same as being harmful.

And that lack of distinction could have a detrimental impact on young readers.

“By putting restrictions on who gets to claim shelf space, school boards are telling marginalized kids — especially those who are LGBTQ+ and/or kids of color — that their very existence is invalid,” Pooja Makhijan reported in Parents magazine last year. “That’s exactly what these book bans are meant to imply.”

At a time when media literacy is devastatingly low, we should be bolstered by the fact that many children and teens are hungry for information, historical narratives and stories from people who both share and don’t share their experiences. The more they learn, the more inquisitive and vocal they are.

That should be encouraged and engaged with, not dismissed, which would only result in a new generation of ignorance.

“If you were the person who helped ban this book, why?” Yeye, 9, asks about “Rosa” in “The ABCs of Book Banning.” “Do you feel like Rosa Parks is a bad person? Do you think that people should not know about her legacy? Why do you choose to do this? I’m just curious.”

The child’s question, of course, goes unanswered. It seems curiosity isn’t what some adults want to deal with anyway.

“The ABCs of Book Banning” is available to stream on Paramount+. “Mary Poppins” is streaming on Disney+.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.