Professional freeride snowboarder Cody Bramwell carves through the deep white powder, left-right-left-right, down the mountainside. He’s snow surfing, a unique, bind-less style of snowboarding invented in Japan in the 1980s.

Rather than focusing on speed and tricks, snow surfing is about finding the flow of the mountain, keeping speed through flat sections and becoming one with the terrain. The sport is best practised in fresh, uncompressed powder, as opposed to crowded ski slopes.

It’s fitting then that the board Bramwell is riding was made in a way that has minimal impact on the pristine nature snow surfing depends upon. Instead of plastic or fibreglass, these snowsurfs are made from old paper.

“I wanted to challenge the status quo and inspire companies to take the step further and look at alternative materials,” says Vincent Skoglund, photographer and co-founder of Swedish audio tech darling Zound Industries (now Marshall Group), who last year founded Papersurf. Skoglund says he is struggling to keep up with orders for the boards, which start at 4495 SEK (€390).

The snowsurfs were built by PaperShell, a Stockholm-based startup that has developed a way to turn paper waste into a durable, high-tech composite it calls “wood metal.”

Beyond snowboards

“It’s like art and magic meets science and biology,” Anders Breitholtz, founder and CEO at PaperShell, tells TNW. “We have created a material that is fun, sleek, stylish and yet flexible, durable, and circular.”

PaperShell’s wood metal can replace high-impact materials like aluminium, fibreglass, and plastics. It can be smooth, matte, or textured. It can be flat, curved, or spherical.

It is heat resistant (even self-extinguishing), water proof, strong, and lighter than fibreglass. It can be used to make furniture, car panels, electronics, facades for buildings, skateboards, and, as we’ve already seen, snowsurfs.

“The design possibilities are, in effect, endless,” says Breitholtz.

To make the material, PaperShell sources craft paper made from waste lignin and cellulose from the timber industry. It then soaks the paper in hemicellulose, a natural polymer found in the cell walls of plants that is readily available as a byproduct from agriculture.

“When you create paper you lose lignin and hemicellulose which are huge waste streams — so we thought, let’s put these back in to make a composite,” says Breitholz.

In essence, it builds back wood.

Learning from nature

Pretty much everything we use and consume on a daily basis depends on materials like metal, minerals, biomass, and fossil fuels. In 2022, the material footprint of the average European — the amount of raw materials dug up to meet our needs — was almost 15 tonnes. This is “simply unsustainable,” as the EU said in a recent report.

The solution? To break our linear take-make-waste consumption habits and make them circular. In a circular economy, products are designed to be reused. When they are no longer useful, instead of waste, they then become a resource for something new, just like in nature.

“Nature has developed mindblowing biointelligence over 3.8 billion years — but humanity seems to be doing its best to undo that,” says Breitholz. “It’s time to start working with the Earth, not against it.”

Today most old wood is incinerated or landfilled, releasing CO2 into the air or, in the case of treated timber, chemicals into the soil.

If PaperShell’s material was to be burnt at the end of its life — a worst case scenario — the company still claims a 90-98% reduction in lifecycle carbon emissions when compared to the same-sized components made of plastics, fibre composites, or metals.

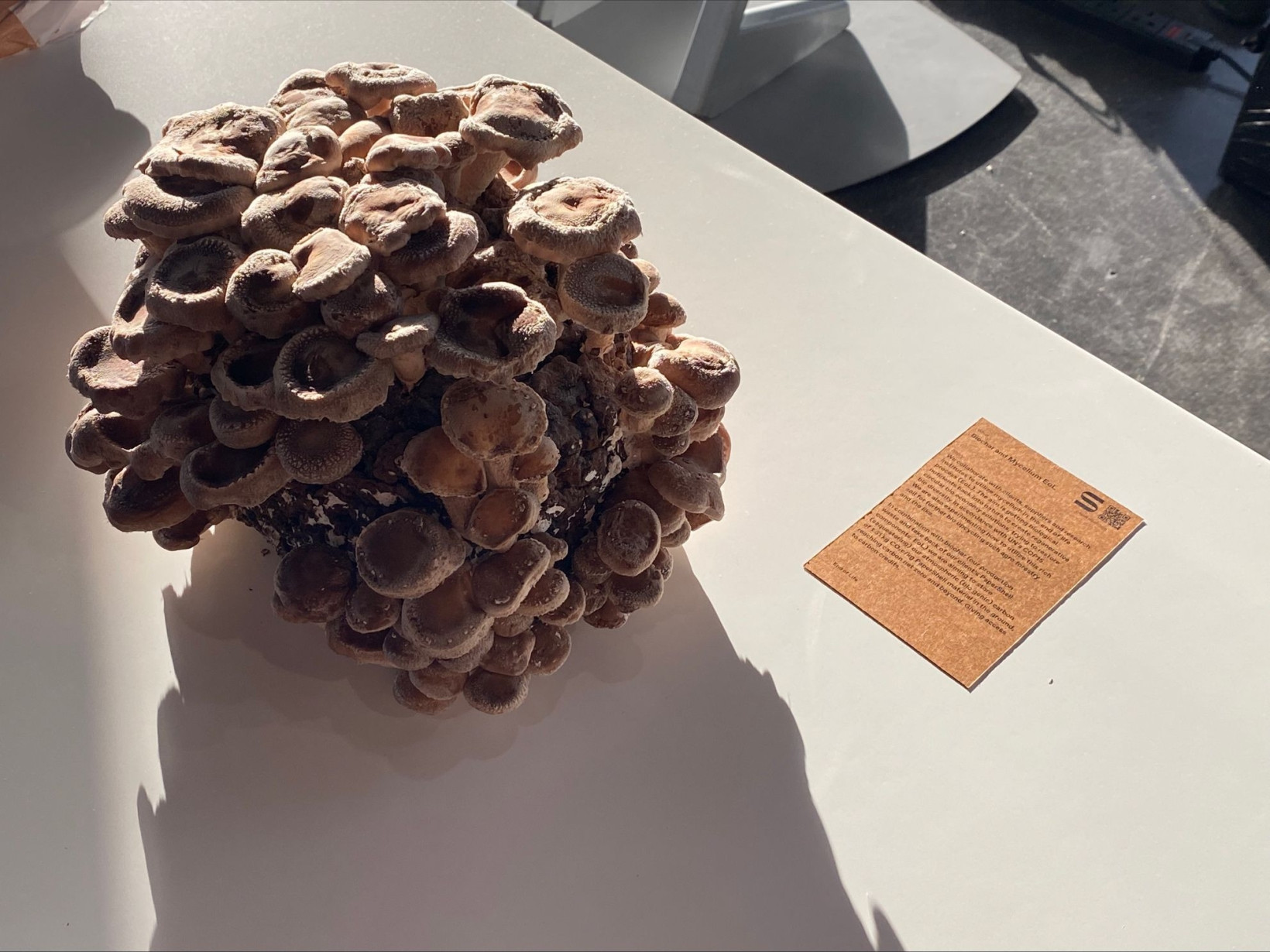

However, for PaperShell, that’s not nearly good enough. The company wants to take the old material and turn it into biochar as a fertiliser to grow new trees. They are also experimenting with mycelium to break down the high-tech wood, return it to the soil, and foster biodiversity.

“We’re teaching the mycelium to break down our material. That’s hardcore. That’s how we should work. If we can tap into that intelligence we’re crazy not to do it,” says Breitholz.

Making it work

Before founding PaperShell in 2021, Breitholz worked for 20 years as a material scout for big corporations and research institutions. His job was to track down the next best, sustainable materials for professionals ranging from carmakers to architects.

For the last three years, the self-proclaimed “crazy founder” and his team have been testing and re-testing their product alongside industry players including EV-maker Polestar and Italian furniture company Arper.

“We had to make sure it actually works in an industrial context, so we teamed up with demanding clients, so we could fail fast and learn quickly,” says Breitholz.

PaperShell has raised €20mn to date, and is currently in the midst of another funding round. Its board includes execs from Swedish appliance manufacturer Electrolux, recycling giant Stena Metall, and design group Interior Input.

The company’s pilot plant, in Tibro, Sweden, has become a testbed for the material. It has also fulfilled some small volume orders — like the Papersurf board. But now, PaperShell is ready to take things up a notch.

Industrialisation

PaperShell has just built a new factory in Tibro which marks a major step up in capacity compared to the current pilot plant — from 600 to 3,2000 square metres of production floor space.

The factory will act as a build-to-print component manufacturing facility. It will use a series of automated press tables to mould different shapes and designs based upon specific orders. The wood metal will act as a material replacement for an existing component — like a panel for a car — or for an entirely new product.

From flat sheets to complex 3D shapes, PaperShell expects to be able to produce up to 700,000 components a year at the new plant. The company is planning to build an even bigger factory in the “near future.”

“This material is actually so simple, so low-tech,” says Breitholz. “But what really excites me is that it has the potential to make an enormous impact, to act as a catalyst for change across so many industries.”

For snowboarder Cody Bramwell, fun is perhaps top of mind. “Shout out to Papersurf, this board is sick!” he said after a session of shredding powder in the Scandinavian backcountry.

Check this video to see how the papersurf was created: